How Corporate Workplaces Hve Changed Over They Years

A shifting economic landscape is driving significant changes in the American workplace. Employment opportunities increasingly lie in jobs requiring higher-level social or belittling skills, or both. Physical or manual skills, equally much in demand equally social or analytical skills some 3 decades agone, are fading in importance. Not coincidentally, employment is ascent faster in jobs calling for greater preparation, whether through educational activity, feel or other forms of training.

These changes have played out surely and steadily in recent decades. A key factor is the decline in manufacturing employment, by about a tertiary just since 1990. Meanwhile, employment in knowledge-intensive and service-oriented sectors, such as education, wellness, and professional and business services, has about doubled. Underlying factors such as globalization, outsourcing of jobs and technological change are among the key forces contributing to the transformation.

Americans are taking annotation of these trends. Respondents to the accompanying Pew Inquiry Center survey report that interpersonal skills, critical thinking, and good writing and communications skills are the near important skills for doing their jobs. And the share of adults ages 25 and older with a bachelor's degree or higher level of instruction increased from 17% in 1980 to 33% in 2015. Most of these workers are engaged in jobs requiring college-level social or belittling skills.

The changes at the workplace take benefited some workers more than than others. The earnings of workers in jobs requiring higher levels of social and belittling skills have risen proportionately more than than the earnings of those in jobs requiring higher levels of physical skills. The growing inequity in earnings by skill type is likewise reflected in the rising inequality in earnings between workers with or without a college education.

The shifting demand for skills may have worked to the benefit of women, since they are more probable than men to be employed in occupations needing higher levels of social and belittling skills, whereas men are relatively more engaged in jobs calling for greater physical and manual skills. Because wages have risen faster in jobs requiring college levels of social and analytical skills, this is probable to have contributed to the shrinking of the gender pay gap from 1980 to 2015.

Determining task skills and grooming

This report analyzes the changing demand for 3 core families of task skills – social, analytical and concrete. Generally speaking, social skills encompass interpersonal skills, written and spoken communications skills, and management or leadership skills. Analytical skills refer to calculator and mathematical skills and the importance of critical thinking. Physical skills pertain to the ability to work with machinery or equipment, manipulate tools, and do physical or manual labor.

The source data for the analysis is the Section of Labor'southward Occupational Information Network (O*NET), a database covering more than than 950 occupations. For each occupation, O*Cyberspace contains ratings of detailed skills on a calibration measuring their importance to job performance, from 1 (non important) to five (extremely important). From the scores of skills listed in O*NET, ratings for a representative handful of skills were selected to represent the broader families of social, belittling and physical skills. For example, negotiating and instructing skills are among those called to stand for social skills. The O*Net ratings for these and related skills are averaged to judge an overall social skill rating for an occupation. A similar process is repeated to determine the belittling and concrete skill rating for a job. Examples of skills chosen to represent analytical abilities are critical thinking and judgment/determination making. Physical abilities are rated based on such skills as handling and moving objects and equipment maintenance.

Ratings for individual occupations are further averaged to obtain an overall rating of the importance of each skill in the American workplace. For example, the average rating of social skills in 2015 was estimated to be 2.96, "important" on the O*NET scale. Thus, occupations with a social skill rating of 2.96 or higher, corresponding to "important," "very important" or "extremely important," are classified equally requiring college levels of social skills. Examples of such occupations are chief executives and registered nurses. A similar process is used to separate jobs requiring average or above-boilerplate analytical skills (e.yard., taxation preparers) or physical skills (east.m., welding, soldering and brazing workers) from other jobs. (See a table available for download online for a complete list of occupations and their skill ratings.)

Information technology is important to notation that a single job may crave loftier levels of more than one skill. For case, about managers and teachers are typically expected to possess college levels of both social and analytical skills. Among the 430 occupations analyzed in item, 206 require average or in a higher place-boilerplate levels of social skills. Moreover, 180 of these 206 occupations also require a college level of analytical skills. Thus, at that place is considerable overlap in the counts of workers in jobs requiring higher levels of social or analytical skills. The overlap is limited betwixt jobs requiring higher levels of physical skills and those requiring higher levels of social or analytical skills.

The preparation required for the operation of a task is likewise rated on a scale of one to five in O*Internet, from petty or no preparation needed to all-encompassing preparation needed. The level of preparation depends on a combination of education, experience and other forms of grooming. The mid-level preparation (rating of three) corresponds to an associate degree or a similar level of vocational training, plus some prior task experience and ane to two years of either formal or informal on-the-job training (eastward.g., electricians). Above-average preparation typically calls for a four-twelvemonth college degree and boosted years of feel and training (eastward.yard., lawyers).

In the midst of a changing workplace, the implicit contract betwixt workers and employers appears to exist loosening. The earnings of workers overall have lagged behind gains in labor productivity since the 1970s.10 Moreover, smaller shares of workers receive health or pension benefits in 2015 than they did in 1980. More than recently, culling employment arrangements, such as contract work, on-phone call work and temporary help agencies, appear to be on the rise.

This chapter focuses on how piece of work has changed for American workers in recent decades. The key event is the shift in employment opportunities, from jobs requiring physical or manual skills to those requiring social or analytical skills. Related to this is the need for higher levels of pedagogy, experience and job training. At the same time, workers must adapt to changes in the broader economic climate. Thus, this section also reports on other key trends in the labor market relating to employment and earnings opportunities, provision of benefits, hours worked, job tenure and piece of work arrangements.

The importance of a given skill to a job is ascertained from the latest ratings in the Section of Labor's Occupational Information Network (O*NET), a comprehensive database whose ratings are based on surveys of workers combined with information received from job analysts. The ratings data from O*NET is matched to occupations listed in the Current Population Survey (CPS), a monthly survey of approximately 55,000 households conducted jointly past the U.Southward. Census Bureau and the Agency of Labor Statistics. The CPS data are then used for the analysis of employment and wage trends in occupations grouped past skill types (see the text box and Methodology for details). The CPS is likewise the source of the data for most of the remaining assay.

The changing demand for job skills and grooming

The types of skills needed in the workplace and the level of preparation required to fulfill a chore may alter over time for two reasons. I possibility is that occupations themselves transform in some manner, perhaps calling for more than computer skills and training over time or using technology to substitute for manual demands. Another possibility is that employment may shift across occupations in response to larger economical and demographic changes. For example, globalization has led to a reduction in the demand for manufacturing workers in the U.South., but the aging of the population has increased the demand for doctors and nurses.

This affiliate focuses on the changing need for job skills and preparation driven past the shift in employment across occupations from 1980 to 2015. Occupations are sorted by importance of a skill type and the level of grooming using the most updated skill ratings in O*NET, principally from inside the by decade. These ratings practice not change over time. However, employment changes over fourth dimension and beyond occupations, driving the overall alter in skills and job training in the workplace.

The demand for job preparation

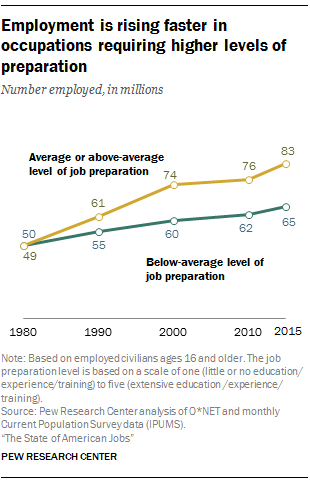

More workers today are in jobs where a higher level of preparation is needed. The number of workers in occupations requiring average to in a higher place-boilerplate didactics, training and experience increased from 49 meg in 1980 to 83 million in 2015, or by 68%. This was more than double the 31% increment in employment, from fifty to 65 meg, in jobs requiring beneath-average instruction, training and experience.

As a result, roughly equally divided in 1980, the articulate majority of workers in today's workforce are in jobs calling for significant grooming. At a minimum, these jobs require an associate degree or a similar level of vocational training, plus some prior job experience and i to ii years of either formal or informal on-the-job training. (Examples of these occupations range from electricians to lawyers. Run into the text box for details.)

Within the grouping of occupations requiring an average to in a higher place-average level of training, the fastest growth in employment is in jobs that typically require at to the lowest degree a iv-yr college caste and considerable to all-encompassing training and experience. Employment in these high-skill occupations, including accountants, teachers, surgeons and the like, increased from 22 million in 1980 to 39 meg in 2015, or by 80%.

The growing demand for higher-skilled jobs is associated with the overall improvement of the education level of the U.S. population. The share of adults 25 and older with a bachelor's degree or higher level of education has nearly doubled in the past 35 years, from 17% in 1980 to 33% in 2015.

The rising of social and analytical skills in the labor market

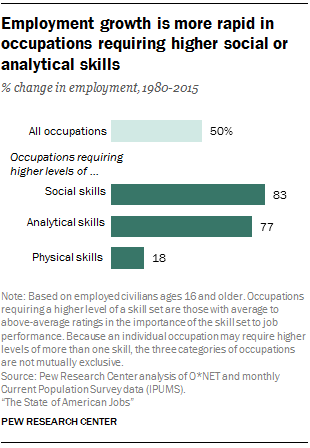

In addition to the level of grooming needed for jobs, the types of skills called for at work are changing. Employment in occupations needing college levels of social or analytical skills increased significantly from 1980 to 2015, but the demand for higher levels of concrete skills has increased only slightly.

Employment in jobs requiring average or in a higher place-average levels of social skills, such as interpersonal, communications or management skills, increased 83% from 1980 to 2015. Meanwhile, employment in jobs requiring higher levels of belittling skills, such as disquisitional thinking and computer use, increased 77%. Examples of jobs needing higher-level social or analytical skills include chief executives, ceremonious engineers, postsecondary teachers and nurses.

In precipitous contrast, employment in jobs requiring higher levels of concrete skills, machinery operation or tool manipulation, barely budged, increasing only eighteen%. Jobs calling for higher levels of physical skills include carpenters, welders, and the like. By comparison, overall employment in the economy increased fifty% from 1980 to 2015.

In terms of numbers, 90 1000000 workers of a full of 148 million were engaged in jobs requiring higher levels of social skills in 2015. At the same time, 86 one thousand thousand workers were in jobs needing boilerplate to in a higher place-average analytical skills in 2015. Employment in jobs requiring higher levels of physical skills added up to 57 meg.

As noted in more than detail in the accompanying text box, in that location is an overlap in these counts of workers considering many jobs phone call for college levels of more than i blazon of skill. For example, managerial or teaching jobs require higher levels of both social and analytical skills. This group of jobs – needing higher levels of both of these skills – is boosting employment by the most in the labor market. More specifically, employment in this select grouping of jobs increased from 39 million in 1980 to 76 million in 2015, an increment of 94%.

While in that location is considerable overlap between social and analytical skills, the need for physical skills in combination with social or analytical skills is limited. Most jobs that crave higher levels of physical skills, such equally carpenters; laundry and dry-cleaning workers; and welding, soldering and brazing workers, do not call for college levels of social and analytical skills. In 2015, at that place were 38 meg workers employed in jobs requiring only higher levels of physical skills. This number was up simply 12% from 1980, when it stood at 34 million.

Employment in jobs requiring college levels of social or belittling skills is full-bodied in more than chop-chop growing sectors of the economy

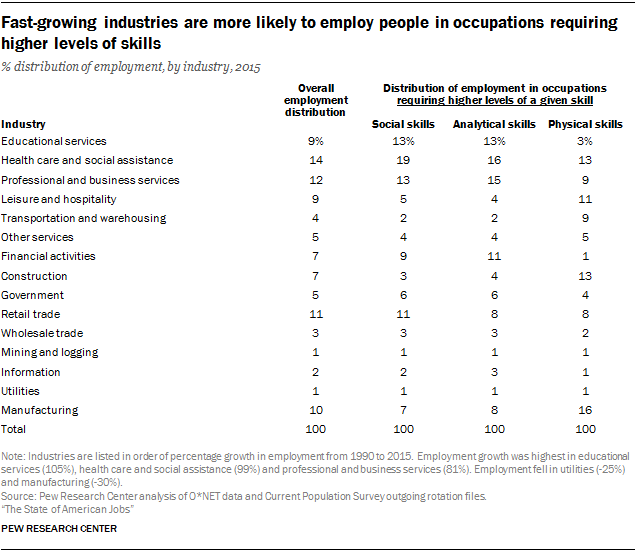

Although each sector in the economic system creates a diverse array of jobs, some occupations are more probable than others to exist establish in sure sectors. For instance, doctors and nurses are principally in the health intendance and social assistance sector, while teachers are concentrated in the educational services sector. Similarly, many production workers, such every bit machinists or tool and die makers, are in manufacturing. For this reason, changes in the economic fortunes of individual sectors are likely to have an influence on the changing needs for skills in the labor market place.

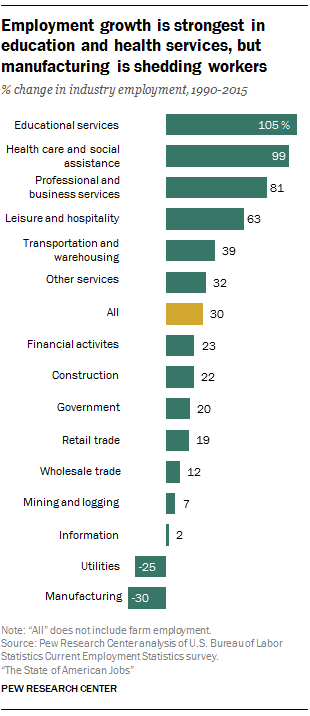

In the past quarter century, there was a precipitous departure in employment growth across industries. From 1990 to 2015, employment doubled in educational services and in health care and social assistance, increasing 105% and 99%, respectively. Employment growth was about as potent in professional and business services (81%).

Overall, these three rapidly growing sectors combined to hire twenty meg more workers from 1990 to 2015, more than than half of the total increase of 32 million. More than importantly, in 2015, 45% of workers in jobs where social skills are in use at a higher level were employed in these 3 sectors, as were 44% of workers in occupations requiring college analytical skills. Thus, the growing importance of social or analytical skills may be linked to the expansion in pedagogy, health, and professional person and business services.

At the same time, the diminishing importance of concrete skills in the economy is partly tied to the pass up of employment in manufacturing. In 2015, 16% of workers in jobs calling for higher levels of physical skills were in the manufacturing sector, compared with ten% of workers overall. But the manufacturing sector shed well-nigh one-3rd of its workforce from 1990 to 2015. Meanwhile, jobs requiring higher levels of physical skills are underrepresented in educational services, health care and social assistance, and professional and business organisation services.11

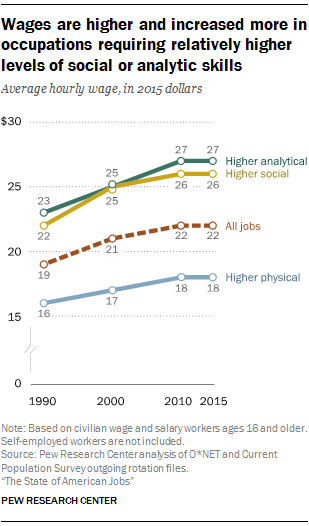

Wages are increasing faster in jobs that require higher levels of social or belittling skills and higher levels of grooming

Jobs requiring higher levels of social or analytical skills generally pay more than jobs requiring higher physical skills. From 1990 to 2015, the boilerplate earnings in jobs more reliant on social or analytical skills have also increased more the average earnings in jobs requiring more intensive physical skills. As a result, the earnings gap between jobs requiring higher levels of social or analytical skills on the one paw and concrete skills on the other has widened over this period.

In 1990, the boilerplate hourly wage of workers in jobs requiring higher analytical skills was $23. This was followed closely by workers in social skill-intensive jobs, who earned $22 per hour. Lagging well behind were workers in physically intensive jobs, who earned $16 per hour, 72% as much equally workers in higher analytical skill jobs. (All wages expressed in 2015 dollars.)

From 1990 to 2015, the average hourly wage in jobs requiring higher analytical skills increased the most, rising 19% to $27.12 The average hourly wage in higher social skill jobs increased xv%, to $26. However, wages for workers in higher physical skill jobs were nearly stagnant, increasing only 7% to $18 per hour. Consequently, workers in physically intensive jobs earned only 65% as much as workers in higher analytical skill jobs in 2015.

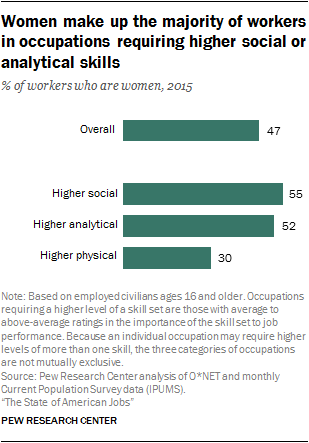

Women may have benefited more men from the changing demand for skills

Women are more likely than men to be employed in occupations where social or analytical skills are relatively more important. In low-cal of the wage trends described in a higher place, this may have helped narrow the gender wage gap in contempo decades.

Overall, women made up 47% of the workforce in 2015. But they were the majority of workers in occupations requiring average or above-average levels of social skills (55%) and workers in jobs requiring college analytical skills (52%). Past dissimilarity, women'due south employment share in occupations requiring higher levels of physical skills was significantly lower (30%).

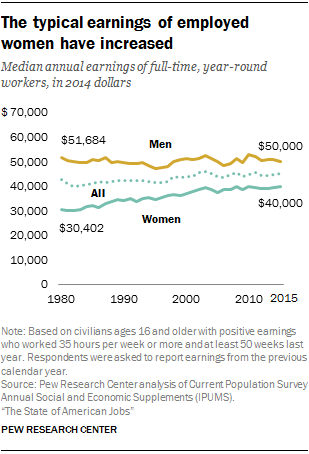

Because of the relatively higher wage associated with jobs requiring higher social or analytical skills, women'due south overrepresentation in these jobs may have helped narrow the gender wage gap. Every bit shown in a later section in this written report, the median annual earnings of full-fourth dimension, year-round working women increased from $xxx,402 in 1980 to $xl,000 in 2015, a gain of 32%. However, full-time, yr-circular working men experienced a 3% loss in earnings as their median annual earnings fell from $51,684 in 1980 to $50,000 in 2015. Equally a consequence, the wage gap between women and men narrowed from near 60 cents on the dollar in 1980 to lxxx cents on the dollar in 2015. (Annual earnings expressed in 2014 dollars.)

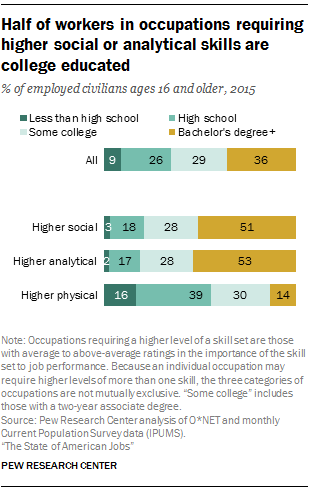

A higher level of teaching is related to the employ of social and analytical skills and other forms of chore preparation

In that location is a strong link between workers' level of didactics and the odds of their working in jobs that crave higher levels of social or analytical skills. Moreover, workers with college levels of education are more than likely to acquire other types of job trainings, acquiring certificates or licenses forth the mode.

In 2015, amidst employed workers overall, more than one-tertiary (36%) had completed at least a four-year college degree program. Merely higher-educated workers accounted for about half of employment in occupations requiring higher social skills (51%) or higher analytical skills (53%). Meanwhile, only xiv% of workers in jobs requiring higher physical skills were college educated. The education level of a majority of workers in concrete-skill jobs was loftier school or less.

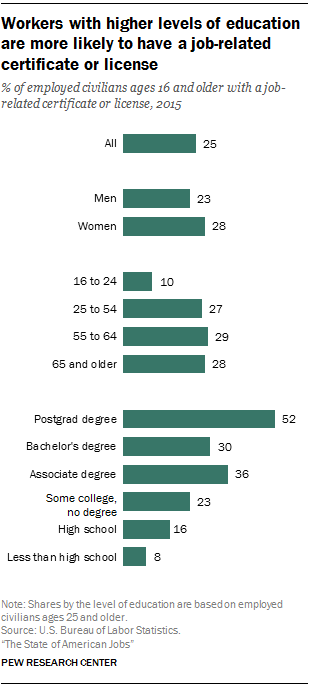

The relationship between college didactics and skills suggests that the need for college-educated workers may keep to grow in the time to come. At the aforementioned time, new government data reveal that workers with higher levels of teaching also have higher levels of task preparation in the class of job-related certificates or licenses.

In 2015, one-in-iv workers (25%) in the U.South. had a job-related document or license, according to new information from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The share was highest among the most educated. More than half (52%) of workers with a postgraduate degree had a job document or license.13 Similarly, workers with a available's degree lonely (30%) and workers with an associate caste (36%) were more likely than average to have a chore-related certificate or license.

There is too a gender gap in the acquisition of certificates and licenses, merely in favor of women. In 2015, women (28%) were more than likely than men (23%) to take certificates or licenses. However, there is about no difference by historic period in the likelihood of having a job certificate or license among workers 25 and older.

The relationship amid education, gender and job training may exist the outcome of which industries and occupations require certificates and licenses. Indeed, industries and occupations vary greatly on this account. About half the workers (47%) in education and health services accept a certificate or license. Just but about ten% of workers in retail trade, information, and leisure and hospitality have a certificate or license. By occupation, certification or license rates are highest in health intendance occupations (77%), legal occupations (68%) and education occupations (56%).

More educated workers and women fared better than others, only employment and earnings prospects overall are fiddling improved

Acquiring new skills and seeking higher levels of chore preparation are not the simply challenges facing workers today. Ii recessions this century, in 2001 and the Great Recession of 2007-09, have set back the employment and earnings potential of many workers by years. Meanwhile, employers have also cutting back on the provision of health and pension benefits. Traditional employment arrangements, while nonetheless the norm, are showing signs of waning. Alternative work arrangements in the class of contract work, on-call work and temporary help agencies appear to exist on the ascension. But in the midst of this, women take raised their engagement with the labor market and the gender wage gap has narrowed in recent decades.

Trends in employment

The employment rate in the U.S. – the share of the population 16 and older that is employed – has been relatively steady since 1980. It peaked nigh recently at 64% in 2000 but returned to its 1980 level (59%) past 2015. The decline in the employment rate since 2000 is linked in function to the aging of the workforce as older workers are less likely to remain in the labor forcefulness. Another important factor is the Great Recession (2007-09), which resulted in a abrupt contraction in the employment charge per unit, from 63% in 2007 to 58% in 2011.

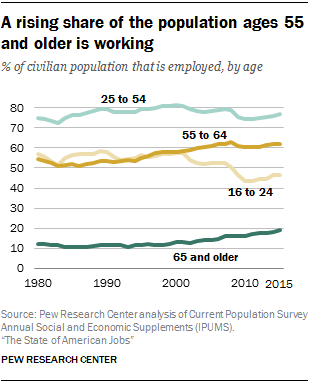

Even though the overall employment rate is currently the same as in 1980, there are some sharp differences across age groups. Younger workers are much less likely to exist working today than they were in 1980, and older workers are laboring on more. Most of this turnaround has happened this century.

Among 16- to 24-yr-olds, less than half (46%) were employed in 2015, compared with 57% in 2000. This trend is driven partly past the fact that a larger share of young adults are enrolled in college, which delays their entry into the workforce. Among 18- to 24-year-olds, 40% were enrolled in higher in 2014, compared with 26% in 1980.

At the other finish of the age spectrum, older adults are staying in the workforce longer than they used to and their employment charge per unit is climbing as a event. The share of adults 65 and older who are employed has risen steadily in contempo decades, climbing from 12% in 1980 to 19% in 2015. The increase was uninterrupted by the Bully Recession. The employment rate for adults ages 55 to 64 has also risen since 1980, but its level in 2015 (62%) was less than its elevation in 2008 (63%).14

Women, too, have greatly increased their presence in the workforce in the by several decades. Some 48% of women 16 and older were employed in 1980, and this share increased to 58% by 2000. During the same period, the employment rate for men held steady at about 70%. Since 2000, the employment rate has fallen for both men and women, although men have experienced a slightly steeper turn down. For men, the employment rate fell from 71% in 2000 to 65% in 2015, or half dozen pct points. During the same catamenia, the employment rate for women decreased from 58% to 54%, a driblet of four percentage points.

Earnings of full-fourth dimension, yr-round workers are fairly flat since 1980 15

American workers overall have not received much of a pay raise from 1980 to 2015. But in that location is a sharp difference in the outcomes for men and women during this time – the earnings of men take fallen, and the earnings of women have risen. Workers with a four-yr college degree and older workers have as well fared meliorate than others.

Afterwards adjusting for inflation, the median earnings for all total-time, year-circular workers increased only 6% from 1980 to 2015, from $42,563 to $45,000 (in 2014 dollars).16 Women, still, experienced a 32% gain in median earnings from 1980 to 2015. In sharp contrast, men experienced a 3% loss in earnings. Every bit a issue, the wage gap betwixt women and men has narrowed from about 60 cents on the dollar in 1980 to fourscore cents on the dollar in 2015.

Along education lines, workers with a four-twelvemonth college or higher level of educational activity are the only grouping to experience a gain in median earnings since 1980. The median earning of a higher-educated worker increased xi% from 1980 to 2015 ($57,764 to $64,000). Meanwhile, the median earnings of workers with bottom education decreased, with the greatest loss experienced by workers who did not complete high schoolhouse. The median for these workers fell from $33,442 in 1980 to $25,000 in 2015, a loss of 25%.

Younger workers are earning significantly less than they did in 1980, but the earnings of older workers have risen. Among full-time, year-round workers, the median earnings of 16- to 24-twelvemonth-olds decreased from $28,131 in 1980 to $25,000 in 2015, a drib of 11%. Meanwhile, the median earnings of workers 65 and older rose 37%, from $36,483 in 1980 to $50,000 in 2015. Workers ages 55 to 64 earned 10% more in 2015 than they did in 1980. The median earnings of workers ages 25 to 54 have remained flat at around $45,000. Full-fourth dimension, year-round workers ages 65 and older used to earn less than their prime-age peers (ages 25 to 54), but now their earnings match those of workers ages 55 to 64 and they are among the ranks of the nation'south highest paid workers.

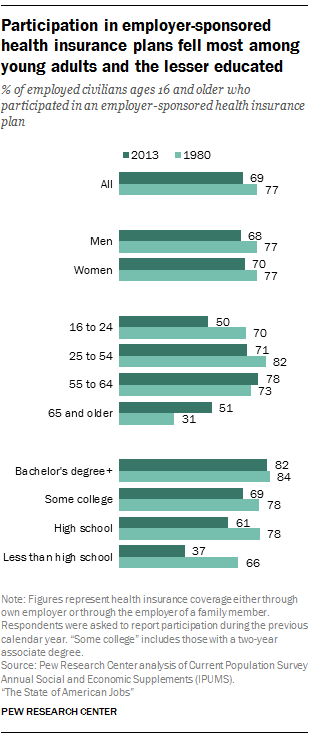

A smaller share of workers are covered by employer-provided benefits 17

Equally earnings overall barely inched up, employee benefits – judged by the share of workers covered by employer-sponsored health insurance or retirement plans – accept eroded since 1980. Only older workers, 55 and older, and, to some extent, workers with a four-year college degree or college level of education have bucked this trend. But even as the coverage of workers has slipped, benefit costs accept causeless a larger share of employee compensation due, in office, to the rise cost of health insurance plans.

Health insurance benefits

As of 2013, employer-sponsored health insurance plans embrace a smaller share of workers than they did in 1980. Most workers get wellness insurance coverage either through their ain employer or the employer of a family member, such every bit a spouse or parent. The share of workers with any employer-sponsored health insurance plan (either through their ain employers or through the employer of a family unit member) vicious from 77% in 1980 to 69% in 2013. The share of workers covered by a health insurance program through their own employer dropped from 62% in 1980 to 51% in 2013.

Among demographic groups, participation in an employer-sponsored wellness program diminished similarly among men and women, from 77% for both in 1980 to 68% for men in 2013 and 70% for women.

The youngest workers (ages 16 to 24) experienced the sharpest decline in employer-sponsored wellness insurance coverage. Seven-in-x young workers in 1980 had health insurance either though their own employer or through the employer of a family member, merely merely half of today's young workers do. The coverage for workers ages 25 to 54 dropped from 82% to 71%. However, older workers, especially those ages 65 and older, are much more than likely to get insurance through an employer than they were several decades ago. The share of workers ages 65 and older with employer-sponsored health insurance increased from 31% to 51%.

Across education groups, workers with a bachelor'south degree or college level of didactics are the just group that did not feel much of a decline in wellness insurance coverage received through employers. Coverage savage among all other pedagogy groups. The sharpest drop was among workers with less than a loftier schoolhouse education, equally the share of these workers with an employer-sponsored health plan fell from 66% in 1980 to 37% in 2013.

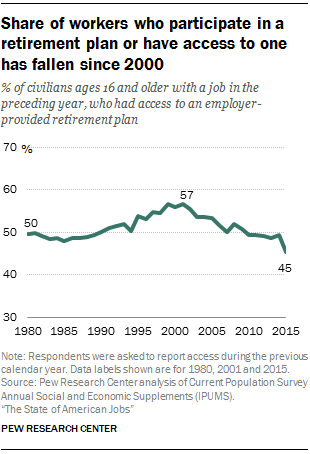

Retirement benefits

In dissimilarity to the long-run decline in wellness insurance benefits, the decrease in retirement benefits is of more recent origin. The share of workers with access to an employer-sponsored retirement programme, whether a traditional pension or a 401(grand)-type plan, peaked most recently at 57% in 2001, up from 50% in 1980.xviii All the same, the share fell to 45% by 2015.

Changes in retirement plan admission also vary across demographic groups, with older workers and women faring better than other groups. In 1980, merely 25% of workers 65 and older had admission to an employer-sponsored retirement plan, only the share increased to 40% in 2015. Overall, retirement benefits are most unremarkably available to workers in their prime number working years. In 2015, the share of workers in a retirement program or with access to ane ranged from 51% among 55- to 64-year-olds to thirty% among 16- to 24-year-olds.

The share of employed men with access to a retirement plan decreased from 53% in 1980 to 44% in 2015. At the same time, the share amid employed women edged up from 45% to 46%. Thus, women at present are more likely than men to have access to a retirement plan.19

Although a smaller share of workers today are covered in employer-sponsored health or retirement plans, the employers' cost of providing these benefits has risen over fourth dimension. This is reflected in the share of benefits in a worker'due south total compensation. The average hourly compensation of employees in June 2016 was $34.05, according to the U.Southward. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Of this, $23.35, or 69%, went to wages and $10.70, or 31%, went to benefits. A quarter century earlier, in 1991, 72% of bounty went to wages and 28% to benefits. The increase in benefit costs derives principally from an increase in insurance benefits (including health insurance). The insurance share in employee compensation is up from vii% in 1991 to 9% in 2016. There is likewise an increase in the share of retirement benefits, from 4% to 5%.

Workers today stay longer with their employer

Chore tenure, measured by how long workers have been with their current employer, has increased in the past iii decades. Most of this increase occurred since 2000. In part, this is due to the rising share of older workers in the labor strength. These workers tend to accept a much longer tenure with their employer. But the economic downturns this century, such every bit the Dandy Recession, may also accept been a factor, making it harder for workers to switch jobs.

The median task tenure for all workers was 4.vi years in 2014, upwardly from 3.five years in 1983. The increase was greater among women (from 3.1 years in 1983 to 4.5 years in 2014) than amidst men (from 4.1 years to 4.7 years over the same menses). Thus, working women now stay with their employer almost as long as their male counterparts do.

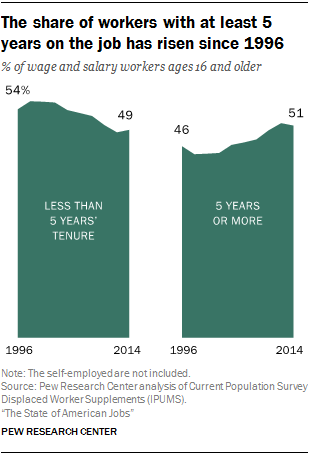

Looked at another way, nigh half of workers (51%) had worked for their current employer five years or longer in 2014, compared with 46% of workers in 1996. Meanwhile, the share of workers who stay with their current employer for one year or less dropped from 26% to 21%.

Older workers tend to have been with their current employer longer than younger workers. In 2012, workers 55 and older had a median tenure greater than 10 years, compared with most 3 years for 25 to 34-twelvemonth-old workers. The job tenure of specific age groups has not changed much since 1996, with the exception of older workers. The share of workers 65 and older who were with the same employer for 5 years or more went upwardly from 67% in 1996 to 76% in 2014, and the share among workers ages 55 to 64 increased from 71% to 75%.

Workers with higher educational activity exercise non take more than job tenure than their lesser-educated counterparts. Among workers 25 and older, those with at least a bachelor's degree had a median job tenure of five.6 years in 2014, compared with v.viii years for those with just a high school diploma. Workers with less than a high schoolhouse educational activity take the shortest tenure among all teaching groups (four.4 years in 2014), and their median tenure has been apartment since 1996.

Americans are working more than overall 20

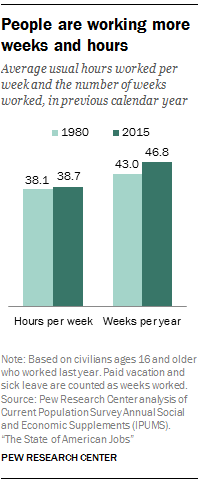

Americans may not be employed in greater shares and their earnings may have risen only modestly, only they are putting in more time at piece of work today than they did in 1980. Most notably, workers are putting in an average of nearly 4 more weeks of piece of work annually, with the average climbing from 43 weeks in 1980 to 46.viii weeks in 2015 (weeks at piece of work include paid vacation and ill get out). The average length of a typical workweek is also up, increasing to 38.seven hours in 2015 from 38.ane hours in 1980.21 Overall, this adds up to an boosted 1 month's worth of work.

This alter is largely driven by the increasing hours and weeks that women devote to the labor market. With respect to hours at piece of work, the average corporeality of time per week by employed women increased from 34.one hours in 1980 to 36.2 hours in 2015, while the average for men was unchanged at virtually 41 hours.

Employed women also significantly increased the weeks they worked on a yearly footing. The average number of weeks worked by working women was 46.2 in 2015, compared with 40.2 in 1980. Weeks worked increased by less among employed men, rise from 45.2 in 1980 to 47.4 in 2015. Equally a result, employed women now piece of work nearly as many weeks annually on average as men.

Another cistron contributing to the growing trend is the sharp increase of piece of work hours among workers 65 and older. The average for workers in this age grouping increased from 29.3 hours per week in 1980 to 33.vii in 2015. Over the same period, workers 65 and older also raised the almanac number of weeks worked from 38.iii to 44.six.

Alternative employment arrangements may exist on the ascent, only fewer workers are self-employed or working multiple jobs

The emergence of services sourced through Uber, Mechanical Turk, Airbnb and other online platforms has given rise to debates nearly whether the workers providing those services are employees or contractors and whether they receive the basic workplace protections and benefits as under conventional piece of work arrangements. Similar concerns environs companies' utilize of contract or temporary workers in lieu of adding workers directly to their payrolls. Although there is bear witness that alternative work arrangements are becoming more prevalent, principally driven by the rise of contract piece of work and independent contractors, the emergence of a sizable online economic system where many workers rely on employment and compensation from "gigs" seems to be some altitude away.

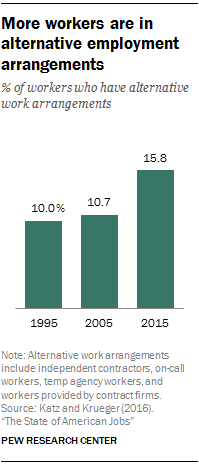

"Alternative employment arrangements" refers to the hiring of workers who are contained contractors or sourced through contract firms, on-call workers, or temporary-help agency workers. The Bureau of Labor Statistics first estimated the share of these workers in overall employment in 1995. At that fourth dimension 10.0% of employed workers were in alternative employment arrangements. This share held steady in the following decade, edging upwards to 10.7% in 2005. More recently, contained researchers who replicated the authorities's survey establish that the share of workers in culling work arrangements had risen to 15.8% in 2015. Thus, nearly 24 million workers currently work in these arrangements.

The bulk of workers with culling employment arrangements are independent contractors, and their share of the workforce rose from 6.three% in 1995 to 8.4% in 2015. The share of contract workers – those hired by a contract company and sent to the customer's worksite – jumped from 1.3% in 1995 to three.1% in 2015. They are now the 2d-largest group of workers with culling work arrangements.

The online, or gig, economy appears still to be in its infancy, at to the lowest degree as measured by its engagement of workers. Co-ordinate to Katz and Krueger (2016), only 0.5% of all workers provided services through online intermediaries such equally Uber in 2015. Another estimate from JPMorgan Hunt Plant finds that one% of adults earned income from work provided through online platforms in whatsoever given month from 2012 to 2015.

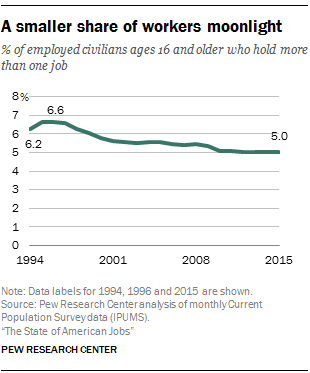

The emergence of the gig worker too fails to materialize in other labor market indicators. The share of workers who moonlight by working more than ane job is on the manner down, falling from more than 6% in the mid-1990s to 5% in 2015. Almost all of this decrease had transpired by 2000, perhaps driven past the economic boom in the 1990s, which may have reduced the need to moonlight. Only the charge per unit has shown no signs of inching up in contempo years.

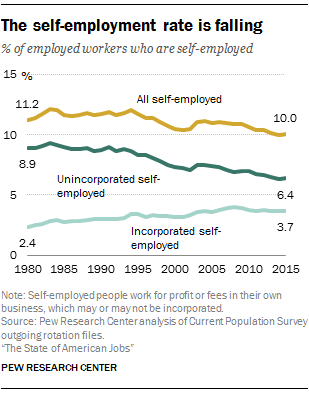

An increase in self-employment is another potential indicator of engagement in the gig economy. But the self-employment rate is also on the decline, falling from eleven.2% in 1980 to 10.0% in 2015. The decrease is entirely due to the falling share of self-employed workers who accept not incorporated their businesses, those more probable to be out on their own.22

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2016/10/06/1-changes-in-the-american-workplace/

Posted by: harrisfromment63.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Corporate Workplaces Hve Changed Over They Years"

Post a Comment